Relationships Series – Starting Again

How well can we truly know another person? Even in our most intimate moments, an invisible, palpable distance remains. This question became the focus of my artistic practice, and it found its deepest expression in my “Relationships Series.”

For those who have followed my work, you’ll know this series began as simple figure studies back in 2010. It quickly evolved into an ongoing meditation on our relationships – about our sense of isolation and vulnerability. It’s been several years since I last added to this body of work, but I’ve found myself persistently called back to it.

Small Lives

I’ve always been fascinated by the intricate, triangular relationship between the artist, the model and the viewer. My work seeks to explore that invisible, yet profound, truth that even in our most cherished connections, we remain distinctly separate.

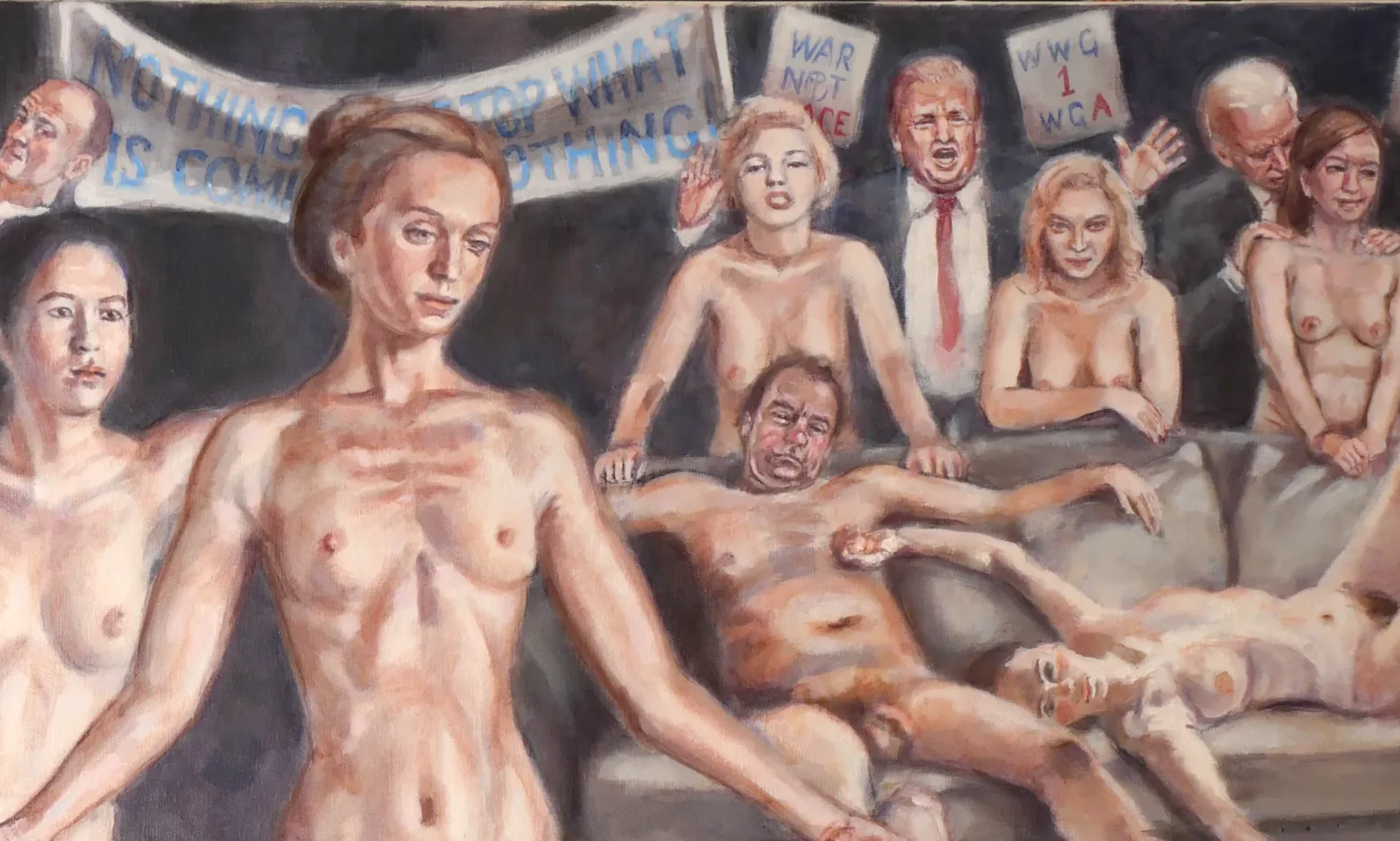

After a long break, I feel a need to explore this theme again, to see how my own understanding of it has shifted with time. For a few years I have been distracted by painting about political upheaval and social injustice. But just as my frustration with the state of the world grows, I have come to realise that there is no bigger subject than our own small lives.

Missing the Spark: The Energy of the Studio

For several years, my artistic focus shifted, and I stepped away from working regularly with models. It took me some time to realize just how much I missed that collaborative relationship—and how much my work benefitted from it.

There is an undeniable energy that a model brings to the room. The studio becomes a silent stage, charged with a quiet intensity. This collaborative energy is a catalyst for inspiration. The subtle shifts in posture, the shared silence, the vulnerability of the experience—it all feeds directly into the work, breathing life into the concepts I’m trying to capture. It’s this dynamic, in-person experience that I’m so eager to return to.

An Invitation to Collaborate

To resume this series, I am now seeking new collaborators. I am looking for people—individuals and couples—who are interested in posing for this work.

In my practice, the model is never just a passive subject. You become a central, active part of that artist-model-viewer triangle. Your presence is the catalyst for the entire conversation.

If this theme resonates with you and you are interested in being part of this new body of work, I invite you to get in touch.

Please [Click Here to Contact Me] with a little about yourself and why you’re drawn to this project.