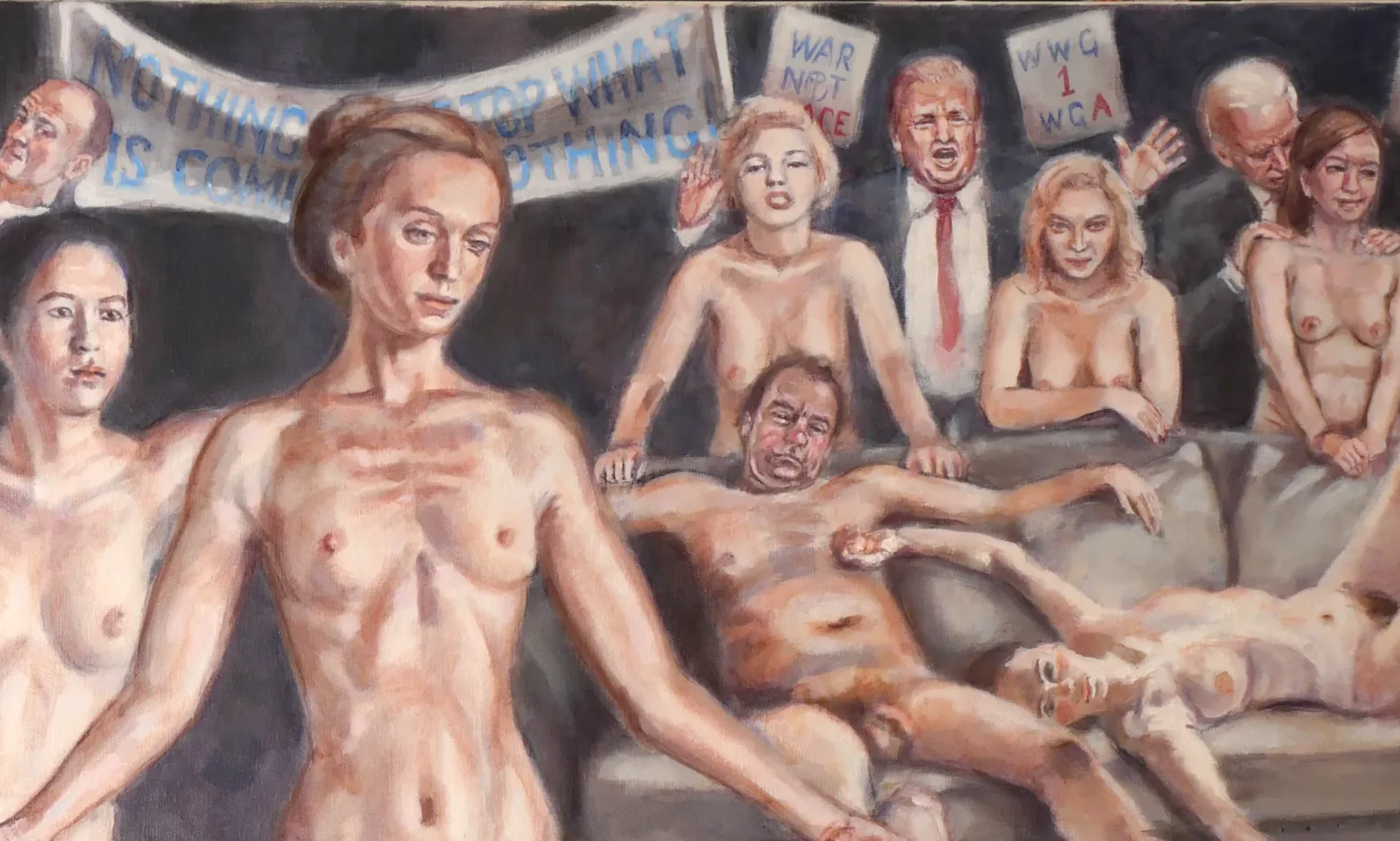

The Painting That Fought Back: A Year-Long Journey to Create ‘The Gleaners’

Some paintings arrive easily, flowing from brush to canvas. This was not one of them. “The Gleaners” took over a year to complete, a journey of false starts, creative blocks, and one crucial breakthrough that transformed the entire piece. It’s a painting about social exclusion, but its creation taught me a lesson about collaboration.

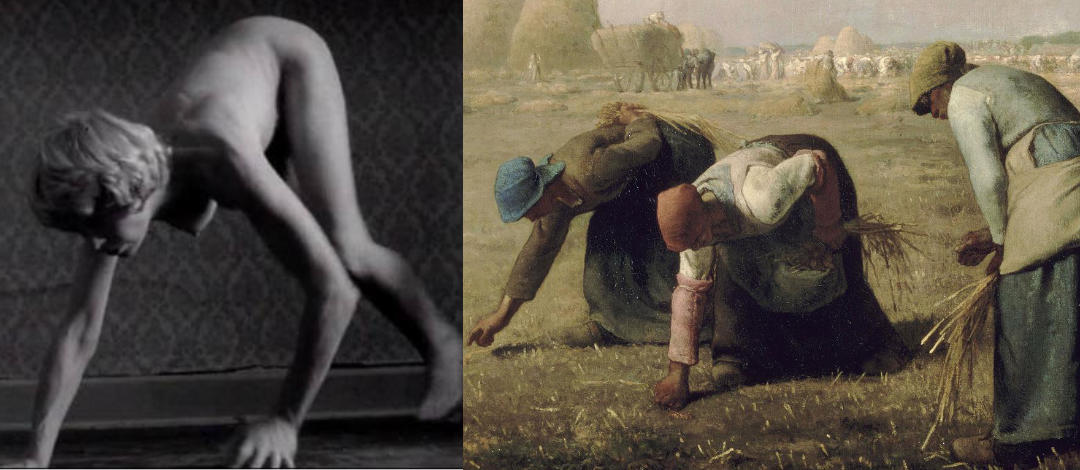

Like many creative projects, it began with a collision of ideas. I wanted to create a contemporary version of Jean-François Millet’s famous painting, “The Gleaners,” to say something about modern inequality. The spark for my figures, however, came from a far stranger place: a still from the 1978 film “The Shout,” where actress Susannah York scurries across the floor like a primeval creature.

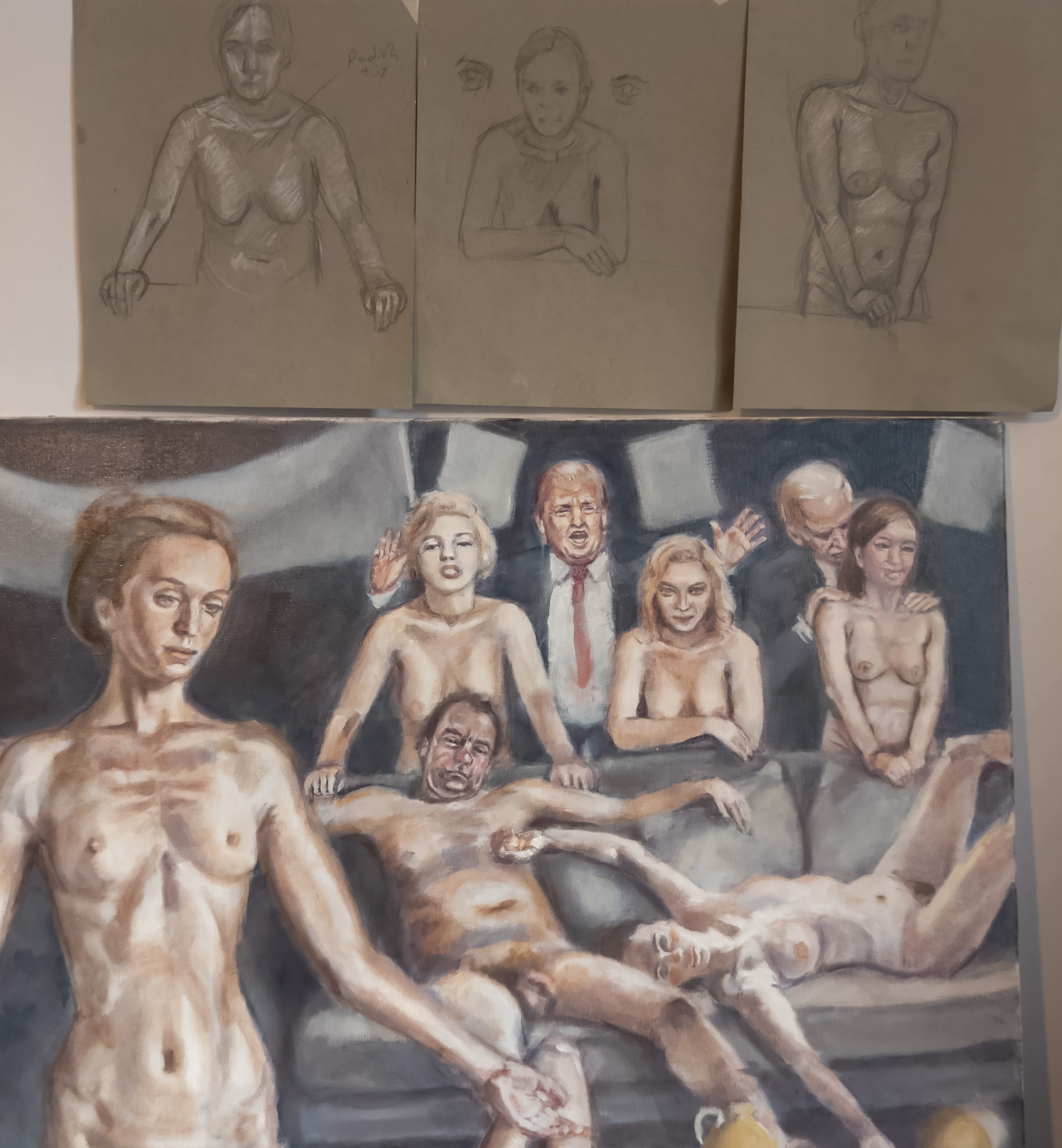

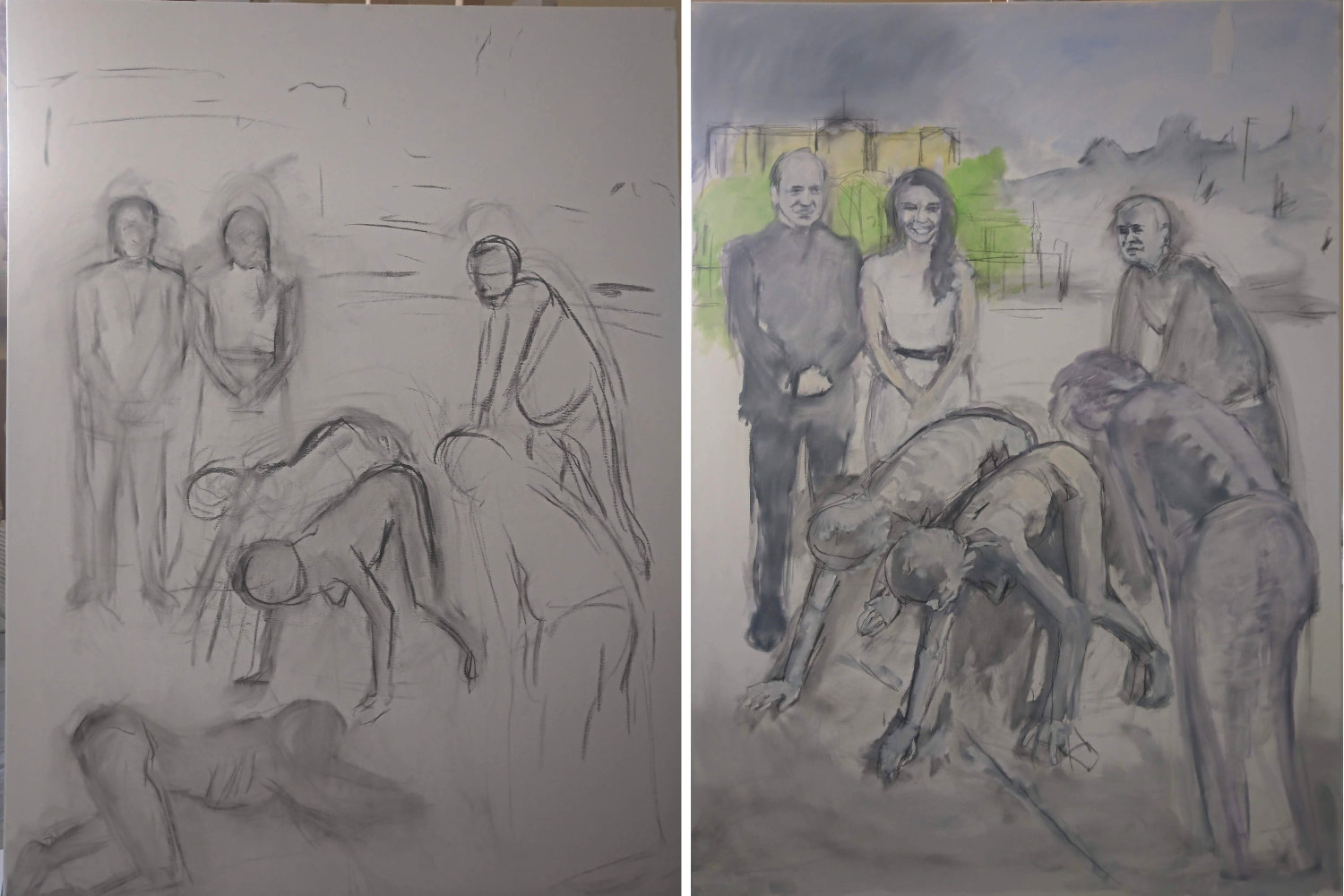

The unsettling, crawling pose felt right. It captured the desperate, overlooked nature of my subjects. I sketched it out, transferred it to canvas, and began to paint.

Early progress was good, but then I hit a wall. For months, the painting languished. I tweaked the composition, changed the colours, and in a moment of near-desperation, even added a SpaceX Starship launching in the background of a desolate wasteland. But nothing worked. The core of the painting—the foreground figures—felt lifeless and wrong. I couldn’t connect with them, and the entire project stalled.

The Breakthrough: A Secret Hidden in a Gainsborough

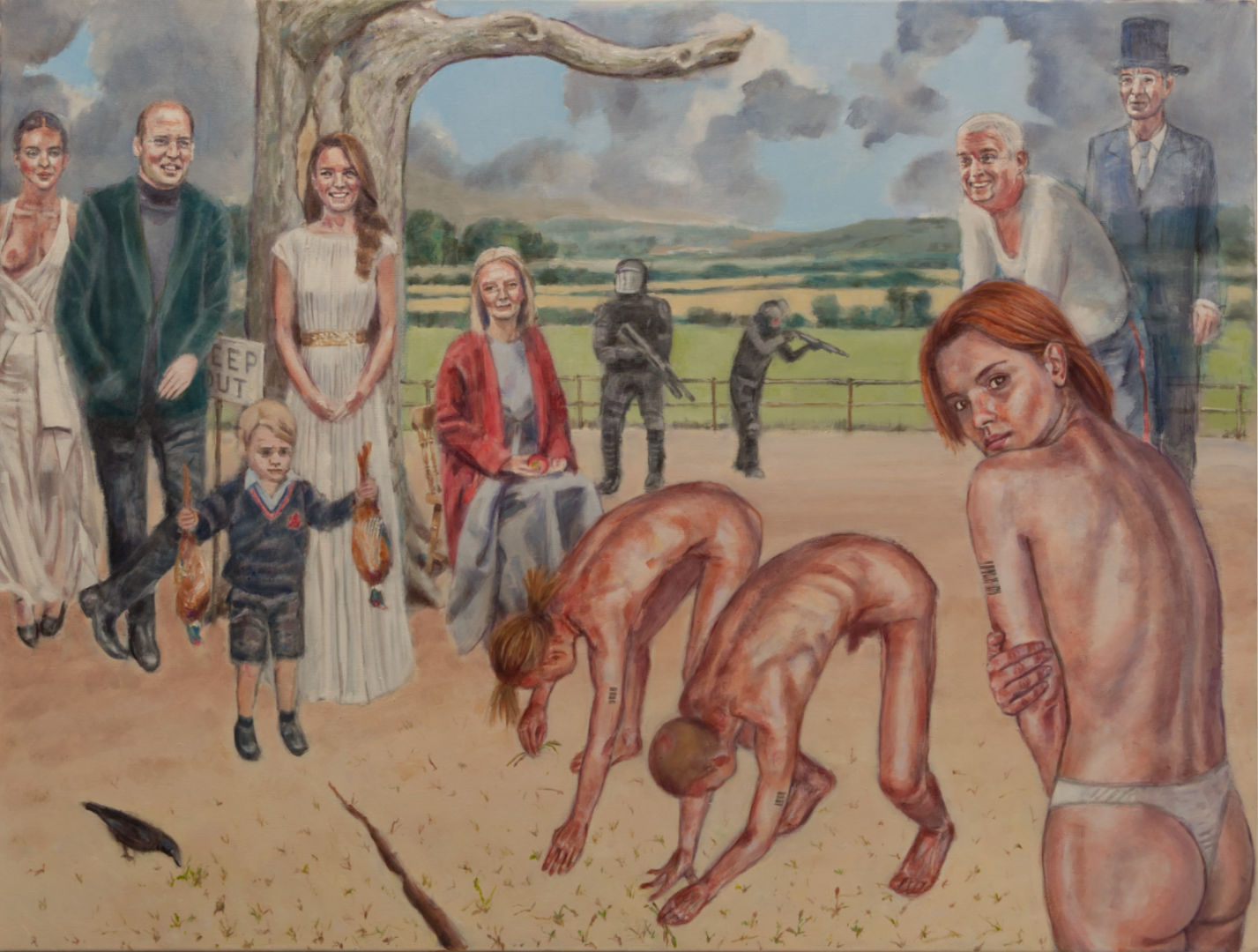

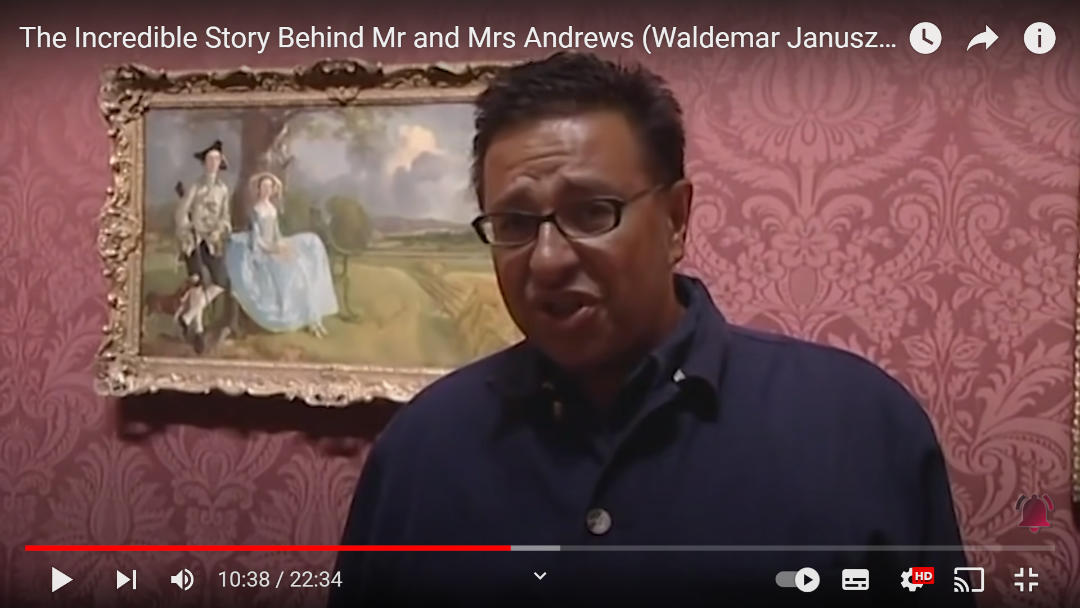

Just when I was ready to give up, a TV documentary changed everything. It was Waldemar Januszczak’s “The Art Mysteries,” exploring Thomas Gainsborough’s “Mr and Mrs Andrews.” Januszczak revealed how the painting subtly references the Enclosure Acts, which fenced off common land and pushed rural people into poverty.

You can watch it on YouTube here.

It was a lightbulb moment. Gainsborough’s composition, with its stark division between the landed gentry and their vast, controlled landscape, gave me the perfect stage for my own story of exclusion. I could fence off the lush green fields and bring the desolate wasteland right to the foreground, trapping my figures within it.

The background was solved. But the central problem remained.

The Final Piece: A Model’s Haunting Gaze

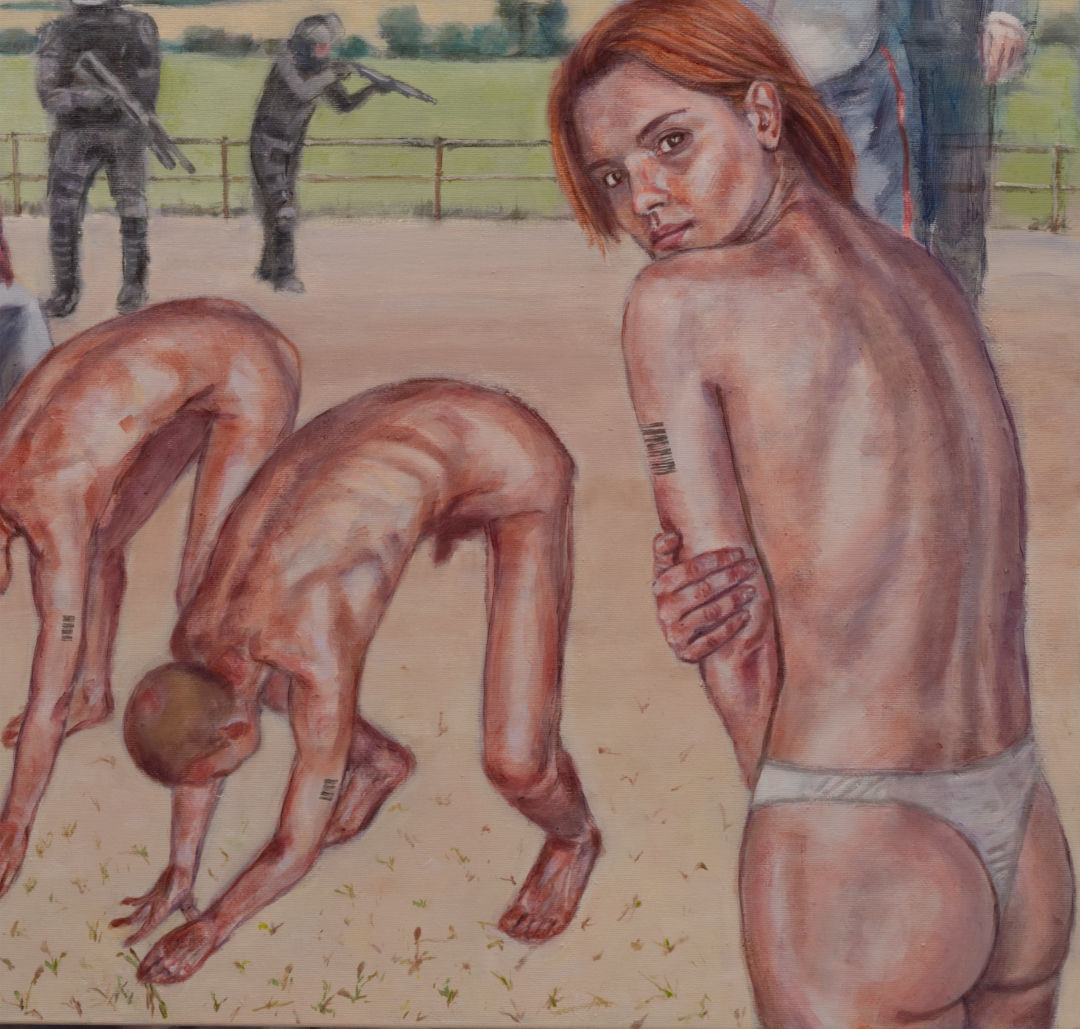

I finally admitted I couldn’t do it alone. My initial vision of emaciated, crawling figures wasn’t translating. I needed a real person.

I put out a call for a life model and found someone perfect for the project. From our first session, everything changed. Working with a real person, collaborating and responding to her presence, breathed life into the work.

We abandoned the original crawling pose. Instead, she offered something far more powerful: a haunting, direct, backward stare.

That stare became the new focal point of the painting. It was defiant, accusatory, and deeply human. The painting was no longer just my idea; it was a collaboration. The final weeks were a joy, and I finished just in time for its debut at the Cluster Contemporary Art Fair.

When I exhibited the painting, I watched as people were drawn in, not by the landscape or the concept, but by the arresting gaze of the foreground figure. It was a detail I had never planned, a gift born from collaboration. It’s a powerful reminder that when you put your easel in front of another person, the art you create is a conversation, not a monologue. And often, the result is something better than you could have imagined alone.